- Home

- Lockhart, Ross

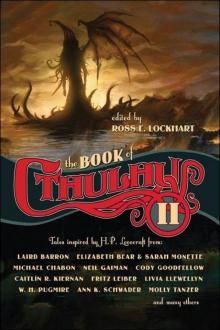

The Book of Cthulhu 2

The Book of Cthulhu 2 Read online

Praise for The Book of Cthulhu:

“Gathering Cthulhu-inspired stories from both 20th and 21st century authors, this collection provides such a huge scope of styles and takes on the mythology that there are sure to be a handful that surprise and inspire horror in even the most jaded reader.”

—Josh Vogt, Examiner.com

“There are no weak stories here—every single one of the 27 entries is a potential standout reading experience. The Book of Cthulhu is nothing short of pure Lovecraftian gold. If fans of H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos don’t seek out and read this anthology, they’re not really fans—it’s that simple.”

—Paul Goat Allen, Explorations: The BN SciFi and Fantasy Blog

“…thanks to the wide variety of contributing authors, as well as Lockhart’s keen understanding of horror fiction and Lovecraft in particular, [The Book of Cthulhu] is the best of such anthologies out there.”

—Alan Cranis, Bookgasm.com

“The Book of Cthulhu is one hell of a tome.”

—Brian Sammons, HorrorWorld.org

“…an impressive tribute to the enduring fascination writers have with Lovecraft’s creation. […] Editor Ross E. Lockhart has done an excellent job of ferreting out estimable stories from a variety of professional, semi-professional, and fan venues […] to establish a sense of continuity and tradition.”

—Stefan Dziemianowicz, Locus

“For anyone who has been a life-long fan of Cthulhu, or anyone looking to start into this universe, The Book of Cthulhu is a wonderful collection.”

—Andrew Keyser, Portland Book Review

“The enduring allure of H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, now nearly a century old, is evident in this representative anthology of modern tales, most of which were written in the last decade. […] To the book’s credit, none of the twenty-seven stories read like slavish Lovecraft pastiche, which makes this volume all the more enjoyable.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“This smorgasbord of Lovecraftian horror should gratify the author’s many fans.”

—Library Journal

Other books edited by Ross E. Lockhart

The Book of Cthulhu

The Book of Cthulhu II © 2012 by Ross E. Lockhart

This edition of The Book of Cthulhu II

© 2012 by Night Shade Books

Cover illustration © 2012 by Mobius9

Cover design and interior graphics by Claudia Noble

Interior layout and design by Amy Popovich

Edited by Ross E. Lockhart

All rights reserved

An extension of this copyright page appears on pages 425-426

First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-59780-435-6

Night Shade Books

Please visit us on the web at

http://www.nightshadebooks.com

For Madeline…

…Chasing the Cats of Ulthar

And for Mike Roth

Friend, Brother, Sounding-board, Fellow Dreamer on the Nightside

Table of Contents

ROSS E. LOCKHART : Introduction

NEIL GAIMAN : Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar

CAITLÍN R. KIERNAN : Nor the Demons Down Under the Sea (1957)

JOHN R. FULTZ : This Is How the World Ends

PAUL TOBIN : The Drowning at Lake Henpin

WILLIAM BROWNING SPENCER : The Ocean and All Its Devices

LIVIA LLEWELLYN : Take Your Daughters to Work

KIM NEWMAN : The Big Fish

CODY GOODFELLOW : Rapture of the Deep

A. SCOTT GLANCY : Once More from the Top

MOLLY TANZER : The Hour of the Tortoise

CHRISTOPHER REYNAGA : I Only Am Escaped Alone to Tell Thee

ANN K. SCHWADER : Objects from the Gilman-Waite Collection

GORD SELLAR : Of Melei, of Ulthar

MARK SAMUELS : A Gentleman from Mexico

W. H. PUGMIRE : The Hands that Reek and Smoke

MATT WALLACE : Akropolis

ELIZABETH BEAR AND SARAH MONETTE : Boojum

JONATHAN WOOD : The Nyarlathotep Event

STANLEY C. SARGENT : The Black Brat of Dunwich

FRITZ LEIBER : The Terror from the Depths

ORRIN GREY : Black Hill

MICHAEL CHABON : The God of Dark Laughter

KARL EDWARD WAGNER : Sticks

LAIRD BARRON : Hand of Glory

Introduction

I can’t help but wonder what H. P. Lovecraft would have made of his continuing literary legacy and current pop culture prominence. On the one hand, I’m sure he would have been pleasantly surprised, once he got past the shock of seeing works he considered disposable pulp entertainments, or worse, stories and fragments he never intended to see the light of day, in print, thriving, and continuing to inspire readers and writers some seventy-five years after his death. After all, tales by the Gent from Providence are widely available in packages ranging from lurid-covered paperbacks and e-books to more scholarly tomes curated and introduced by well-respected author/editors like Joyce Carol Oates and Peter Straub. HPL possibly would have affected embarrassment over the scholarly attention afforded his fiction by the likes of Houellebecq, Joshi, and Price, but I’m sure he would also have felt a swell of pride over the recognition by these writers, and of his place in American letters, and his recognition as, as Fritz Leiber described him, “the Copernicus of the horror story.”

On the other hand, there is also the matter of Lovecraft’s place in popular culture. What would HPL have remarked upon discovering that his Jeffrey Coombs-voiced cartoon avatar—H. P. Hatecraft—has solved mysteries alongside the Scooby-Doo gang (and a cartoon avatar of Harlan Ellison®)? Would he have been offended or amused upon seeing South Park’s Cartman team-up with Cthulhu against Justin Beiber to a My Neighbor Tortoro-inspired soundtrack? Would he have tried for a high score in Cthulhu Saves the World? Likewise, what might HPL have made of his recent cinematic legacy, from the titillating gore-fests of Stuart Gordon to the retro reconstructions of the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society to the recently-aborted multi-million-dollar Guillermo del Toro adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness?

Regardless of what Lovecraft himself would have taken away from the various offshoots his fiction has inspired over the decades, a handful of simple facts remain. Today, H. P. Lovecraft is more popular than ever, and generations of new readers have discovered—and continue to discover—the fictional universe he created, and the philosophy of cosmicism he pioneered. Authors continue to draw inspiration from Lovecraft’s life and works, setting their own tales of cosmic horror, pitting scholars, dreamers, and occult investigators against terrifying cosmic indifference and the machinations of the Great Old Ones in Lovecraftian venues such as Arkham, Dunwich, and Innsmouth.

Part of the continuing appeal of Lovecraft’s universe of cosmic terror is that HPL, unlike fantasists such as J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, actively encouraged writers he admired or mentored to play in his creation. By doing this, HPL inadvertently created an open source fantastic universe unlike any other, ultimately grounded in the modern world, but enriched by secret histories and weird cults, and populated by ghouls, night-gaunts, and Elder Things. And while some focus only on the outlying horrors of the Cthulhu Mythos, it is Lovecraft’s overarching sense of connectedness, bridging Randolph Carter’s Dunsanian oneiric journey to Kadath and beyond with the still-shocking schlock of “Herbert West—Reanimator.” It all integrates.

But it takes more than a few unpronounceable names, moldy tomes, and tentacles to successfully write a story in the Lovecraftian mode. To succeed, an author must not only internalize Lovecraft’s materialistic meme, but must innovate, rather than imitate, recasting Grandpa T

heobald’s broad creation, unmooring it from the social mores of Lovecraft’s time and truly making it their own. The tales collected in this volume—and the previous—do just that.

But now, the stars grow right, and the sleeper stirs. Welcome, readers to The Book of Cthulhu II. Iä! Iä! Cthulhu Fhtagn!

Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar

Neil Gaiman

BENJAMIN LASSITER was coming to the unavoidable conclusion that the woman who had written A Walking Tour of the British Coastline, the book he was carrying in his backpack, had never been on a walking tour of any kind, and would probably not recognise the British coastline if it were to dance through her bedroom at the head of a marching band, singing “I’m the British Coastline” in a loud and cheerful voice while accompanying itself on the kazoo.

He had been following her advice for five days now and had little to show for it, except blisters and a backache. All British seaside resorts contain a number of bed-and-breakfast establishments, who will be only too delighted to put you up in the “off-season” was one such piece of advice. Ben had crossed it out and written in the margin beside it: All British seaside resorts contain a handful of bed-and-breakfast establishments, the owners of which take off to Spain or Provence or somewhere on the last day of September, locking the doors behind them as they go.

He had added a number of other marginal notes, too. Such as Do not repeat not under any circumstances order fried eggs again in any roadside cafe and What is it with the fish-and-chips thing? and No they are not. That last was written beside a paragraph which claimed that, if there was one thing that the inhabitants of scenic villages on the British coastline were pleased to see, it was a young American tourist on a walking tour.

For five hellish days, Ben had walked from village to village, had drunk sweet tea and instant coffee in cafeterias and cafes and stared out at grey rocky vistas and at the slate-coloured sea, shivered under his two thick sweaters, got wet, and failed to see any of the sights that were promised.

Sitting in the bus shelter in which he had unrolled his sleeping bag one night, he had begun to translate key descriptive words: charming he decided, meant nondescript; scenic meant ugly but with a nice view if the rain ever lets up; delightful probably meant We’ve never been here and don’t know anyone who has. He had also come to the conclusion that the more exotic the name of the village, the duller the village.

Thus it was that Ben Lassiter came, on the fifth day, somewhere north of Bootle, to the village of Innsmouth, which was rated neither charming, scenic nor delightful in his guidebook. There were no descriptions of the rusting pier, nor the mounds of rotting lobster pots upon the pebbly beach.

On the seafront were three bed-and-breakfasts next to each other: Sea View, Mon Repose and Shub Niggurath, each with a neon VACANCIES sign turned off in the window of the front parlour, each with a CLOSED FOR THE SEASON notice thumbtacked to the front door.

There were no cafes open on the seafront. The lone fish-and-chip shop had a CLOSED sign up. Ben waited outside for it to open as the grey afternoon light faded into dusk. Finally a small, slightly frog-faced woman came down the road, and she unlocked the door of the shop. Ben asked her when they would be open for business, and she looked at him, puzzled, and said, “It’s Monday, dear. We’re never open on Monday.” Then she went into the fish-and-chip shop and locked the door behind her, leaving Ben cold and hungry on her doorstep.

Ben had been raised in a dry town in northern Texas: the only water was in backyard swimming pools, and the only way to travel was in an air-conditioned pickup truck. So the idea of walking, by the sea, in a country where they spoke English of a sort, had appealed to him. Ben’s hometown was double dry: it prided itself on having banned alcohol thirty years before the rest of America leapt onto the Prohibition bandwagon, and on never having got off again; thus all Ben knew of pubs was that they were sinful places, like bars, only with cuter names. The author of A Walking Tour of the British Coastline had, however, suggested that pubs were good places to go to find local colour and local information, that one should always “stand one’s round”, and that some of them sold food.

The Innsmouth pub was called The Book of Dead Names and the sign over the door informed Ben that the proprietor was one A. Al-Hazred, licensed to sell wines and spirits. Ben wondered if this meant that they would serve Indian food, which he had eaten on his arrival in Bootle and rather enjoyed. He paused at the signs directing him to the Public Bar or the Saloon Bar, wondering if British Public Bars were private like their Public Schools, and eventually, because it sounded more like something you would find in a Western, going into the Saloon Bar.

The Saloon Bar was almost empty. It smelled like last week’s spilled beer and the day-before-yesterday’s cigarette smoke. Behind the bar was a plump woman with bottle-blonde hair. Sitting in one corner were a couple of gentlemen wearing long grey raincoats and scarves. They were playing dominoes and sipping dark brown foam-topped beerish drinks from dimpled glass tankards.

Ben walked over to the bar. “Do you sell food here?”

The barmaid scratched the side of her nose for a moment, then admitted, grudgingly, that she could probably do him a ploughman’s.

Ben had no idea what this meant and found himself, for the hundredth time, wishing that A Walking Tour of the British Coastline had an American-English phrase book in the back. “Is that food?” he asked.

She nodded.

“Okay. I’ll have one of those.”

“And to drink?”

“Coke, please.”

“We haven’t got any Coke.”

“Pepsi, then.”

“No Pepsi.”

“Well, what do you have? Sprite? 7UP? Gatorade?”

She looked blanker than previously. Then she said, “I think there’s a bottle or two of cherryade in the back.”

“That’ll be fine.”

“It’ll be five pounds and twenty pence, and I’ll bring you over your ploughman’s when it’s ready.”

Ben decided as he sat at a small and slightly sticky wooden table, drinking something fizzy that both looked and tasted a bright chemical red, that a ploughman’s was probably a steak of some kind. He reached this conclusion, coloured, he knew, by wishful thinking, from imagining rustic, possibly even bucolic, ploughmen leading their plump oxen through fresh-ploughed fields at sunset and because he could, by then, with equanimity and only a little help from others, have eaten an entire ox.

“Here you go. Ploughman’s,” said the barmaid, putting a plate down in front of him.

That a ploughman’s turned out to be a rectangular slab of sharp-tasting cheese, a lettuce leaf, an undersized tomato with a thumb-print in it, a mound of something wet and brown that tasted like sour jam, and a small, hard, stale roll, came as a sad disappointment to Ben, who had already decided that the British treated food as some kind of punishment. He chewed the cheese and the lettuce leaf, and cursed every ploughman in England for choosing to dine upon such swill.

The gentlemen in grey raincoats, who had been sitting in the corner, finished their game of dominoes, picked up their drinks, and came and sat beside Ben. “What you drinking?” one of them asked, curiously.

“It’s called cherryade,” he told them. “It tastes like something from a chemical factory.”

“Interesting you should say that,” said the shorter of the two. “Interesting you should say that. Because I had a friend worked in a chemical factory and he never drank cherryade.” He paused dramatically and then took a sip of his brown drink. Ben waited for him to go on, but that appeared to be that; the conversation had stopped.

In an effort to appear polite, Ben asked, in his turn, “So, what are you guys drinking?”

The taller of the two strangers, who had been looking lugubrious, brightened up. “Why, that’s exceedingly kind of you. Pint of Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar for me, please.”

“And for me, too,” said his friend. “I could murder a Shoggoth’s. ’Ere, I bet that would ma

ke a good advertising slogan. ‘I could murder a Shoggoth’s.’ I should write to them and suggest it. I bet they’d be very glad of me suggestin’ it.”

Ben went over to the barmaid, planning to ask her for two pints of Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar and a glass of water for himself, only to find she had already poured three pints of the dark beer. Well, he thought, might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb, and he was certain it couldn’t be worse than the cherryade. He took a sip. The beer had the kind of flavour which, he suspected, advertisers would describe as full-bodied, although if pressed they would have to admit that the body in question had been that of a goat.

He paid the barmaid and manoeuvered his way back to his new friends.

“So. What you doin’ in Innsmouth?” asked the taller of the two. “I suppose you’re one of our American cousins, come to see the most famous of English villages.”

“They named the one in America after this one, you know,” said the smaller one.

“Is there an Innsmouth in the States?” asked Ben.

“I should say so,” said the smaller man. “He wrote about it all the time. Him whose name we don’t mention.”

“I’m sorry?” said Ben.

The little man looked over his shoulder, then he hissed, very loudly, “H. P. Lovecraft!”

“I told you not to mention that name,” said his friend, and he took a sip of the dark brown beer. “H. P. Lovecraft. H. P. bloody Lovecraft. H. bloody P. bloody Love bloody craft.” He stopped to take a breath. “What did he know. Eh? I mean, what did he bloody know?”

Ben sipped his beer. The name was vaguely familiar; he remembered it from rummaging through the pile of old-style vinyl LPs in the back of his father’s garage. “Weren’t they a rock group?”

“Wasn’t talkin’ about any rock group. I mean the writer.”

The Book of Cthulhu 2

The Book of Cthulhu 2